“ALL the North Sea’s people are connected to each other,” muses Hans de Boer, president of VNO-NCW, the Dutch business lobby, as he gazes from his 12th-floor office in The Hague. It is not a bad place for a Dutchman to consider the consequences of Brexit. The port of Rotterdam, Europe’s busiest, is just visible in the morning haze. Eighty thousand Dutch firms trade with Britain; 162,000 lorries thunder between the two countries each year. Rabobank, a Dutch lender, calculates that even a soft Brexit could lop 3% off GDP by 2030. Bar Ireland, no country will suffer more. “Brexit was not our preferred option,” offers Mr de Boer, drily.

“ALL the North Sea’s people are connected to each other,” muses Hans de Boer, president of VNO-NCW, the Dutch business lobby, as he gazes from his 12th-floor office in The Hague. It is not a bad place for a Dutchman to consider the consequences of Brexit. The port of Rotterdam, Europe’s busiest, is just visible in the morning haze. Eighty thousand Dutch firms trade with Britain; 162,000 lorries thunder between the two countries each year. Rabobank, a Dutch lender, calculates that even a soft Brexit could lop 3% off GDP by 2030. Bar Ireland, no country will suffer more. “Brexit was not our preferred option,” offers Mr de Boer, drily.Dutch governments spent the 1950s and 1960s trying to get their British friends into the European club; when Britain voted to leave, in June 2016, some wondered if they might drag the Dutch out with them. The EU’s economic and migration traumas had tested the patience of voters for years, and Mark Rutte, prime minister since 2010, seemed unwilling to make the case for Europe. Eurosceptic strains found a vessel in Geert Wilders, a platinum-haired race-baiter who urged “Nexit”. Just over a year ago, with an election approaching, Europeans braced for trouble.

Get our daily newsletter

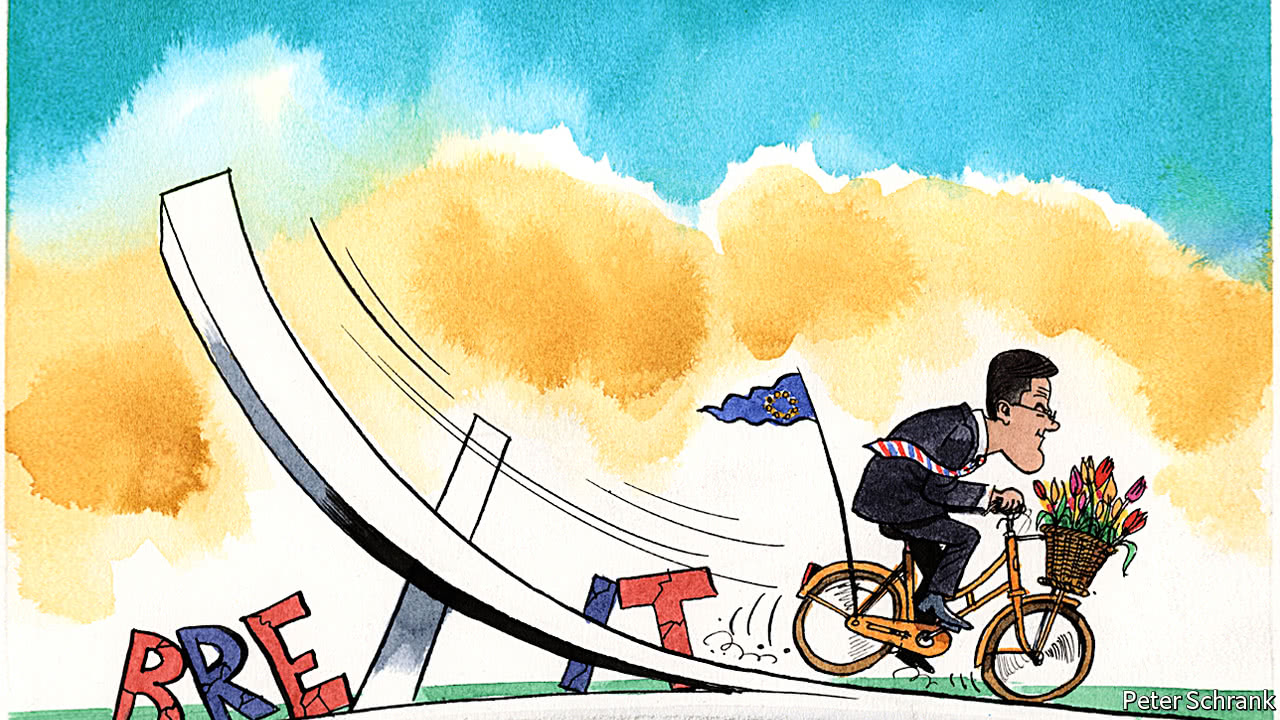

What happened next was more interesting. Mr Rutte won the election, although Mr Wilders’s success forced him into a four-party coalition with a tiny majority. But rather than continue to play the spoiler, Mr Rutte, with some prodding from his advisers, joined the European debate with a vigour few knew was in him. In early March he visited Berlin to deliver a detailed speech on the EU, his first major intervention since taking office in 2010. Soon afterwards the Dutch and seven like-minded small northern and eastern European countries (one official calls it the “bad-weather coalition”) issued a paper laying out a common EU vision.

Arguably, there is no substantive policy change involved. The Dutch still want to limit risk-sharing and common spending in the euro zone, and to boost intra-EU trade. With a Calvinist finger-wag, they urge governments to mind their own yard before seeking common solutions. But Mr de Boer says this is about reassuring Dutch voters rather than attacking the EU. And the Berlin speech marks a change of style for a prime minister long reluctant to engage in European debates. Mr Rutte used to return from EU summits moaning about windbaggery. Now he jumps right in. “I’ve never seen him so pro-European,” says a colleague.

To explain why, Mr Rutte notes cheerfully that Brexit requires the Dutch to recalibrate their four-century diplomatic balancing-act between France, Germany and Britain. That means two things. First, an unabashed commitment to Europe. The Dutch want the EU to forge a strong trading relationship with Britain, but will not break ranks to help bring it about. Second, a willingness to form ad hoc coalitions on specific issues. Mr Rutte reels some off: the Germans on migration, trade and the euro; some central European countries on the EU internal market; the French on climate change. “Brexit is a wake-up call,” says Ben Knapen, a former Europe minister. Where the Dutch were often content to let Britain take the lead, now they must step up themselves.

In part this is a hedging strategy against a big-power stitch-up. Fear of being steamrollered by the Franco-German engine, now cranking into gear again, sits in the DNA of Dutch diplomats. Yet they are cautiously optimistic that the Germans will not sell them out on matters like the EU budget or euro-zone reform. Indeed, the Germans are happy to have the group of eight as attack dogs because it places them at the centre of the debate. Peter Altmaier, Germany’s economy minister and a confidant of Angela Merkel, has lent the bad-weather coalition his tacit support.

But Mr Rutte is also investing in Emmanuel Macron. After twice hosting Mr Rutte in Paris, France’s president dropped into The Hague last week. French-Dutch enmity runs deep, especially on the euro zone; the Dutch want stronger national buffers to protect against crises, whereas Mr Macron is impatient to build supranational bodies and a hefty common budget. Mr Rutte acknowledges the differences, but suggests that if he and Mr Macron can strike a deal, the rest of the EU may follow in their wake. (Germany might have something to say about that.) Trade-loving Dutch diplomats used to shudder at Mr Macron’s call for a “Europe that protects”. Now, glancing nervously at rapacious Chinese investment, Russian menaces, Donald Trump’s tariffs and the terrorist threat, they wonder if he has a point.

Not a mouse, and roaring

It is a delicate moment for the Dutch. Brexit eliminates an ally, but creates an opportunity to take the initiative. The renewal of the Franco-German relationship presents a hazard, but also a chance to shape the debate. The EU’s deal with Turkey to stem illegal immigration in 2016, which the Dutch helped construct, taught Mr Rutte that there is a role for European action in fixing national problems. Dutch officials admit that they are still finding their feet in this new world. But there is a fresh swagger to their diplomacy. Mr Rutte bristles at any suggestion that his country is “small”.

Nonetheless, he must be careful to avoid a backlash at home, which makes him careful what he says. MPs, including members of the ruling parties, and the media are alert to the merest hint of being dragged into an EU “transfer union”. The Dutch are increasingly weary of eastern Europeans who refuse refugees but lap up EU subsidies. The Eurosceptic right also has a new champion in Thierry Baudet, a well-groomed, piano-playing political entrepreneur. Mr Baudet is dismissed by the establishment as a pseud-in-a-suit, but his calls for the Dutch to leave the EU resonate. His Forum for Democracy has vaulted past Mr Wilders in the polls.

That alone will force Mr Rutte to take a tough line in the coming EU debates on asylum reform, the budget and the euro zone. For many Europeans, the Dutch will only ever be a stalwart member of the awkward squad. But having spent so long on the sidelines, they are at least now taking part.This article appeared in the Europe section of the print edition under the headline "Going Dutch"

0 Response to "How the Dutch will take Britain’s place in Europe"

Post a Comment