Stephen Chen

The system, which involves an enormous network of fuel-burning chambers installed high up on the Tibetan mountains, could increase rainfall in the region by up to 10 billion cubic metres a year – about 7 per cent of China’s total water consumption – according to researchers involved in the project. Tens of thousands of chambers will be built at selected locations across the Tibetan plateau to produce rainfall over a total area of about 1.6 million square kilometres (620,000 square miles), or three times the size of Spain. It will be the world’s biggest such project.

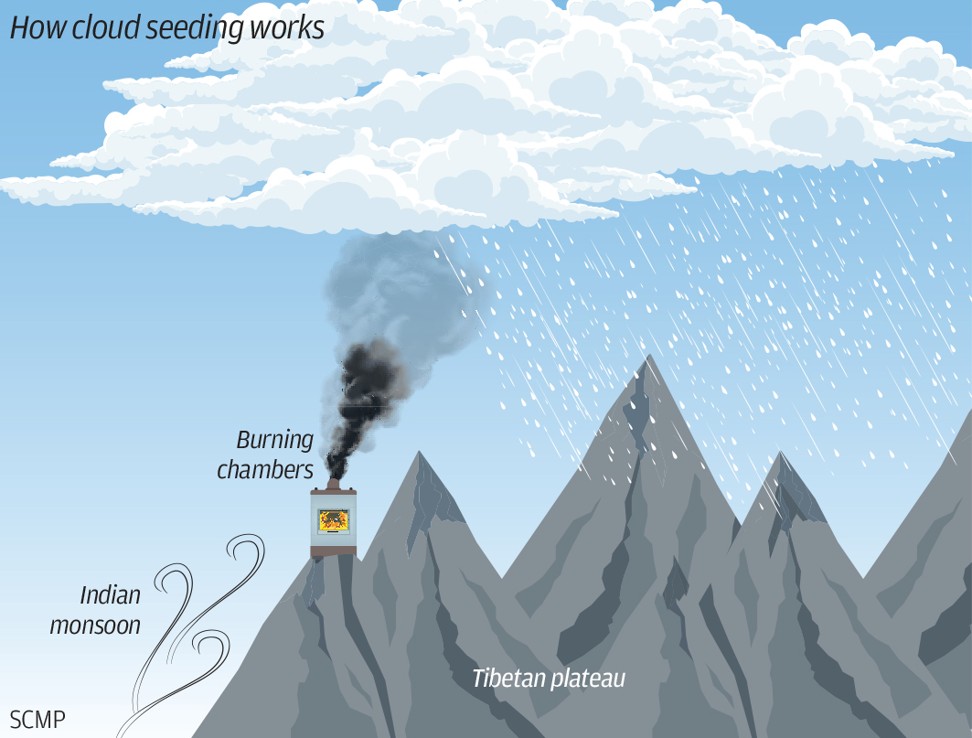

The system, which involves an enormous network of fuel-burning chambers installed high up on the Tibetan mountains, could increase rainfall in the region by up to 10 billion cubic metres a year – about 7 per cent of China’s total water consumption – according to researchers involved in the project. Tens of thousands of chambers will be built at selected locations across the Tibetan plateau to produce rainfall over a total area of about 1.6 million square kilometres (620,000 square miles), or three times the size of Spain. It will be the world’s biggest such project.The chambers burn solid fuel to produce silver iodide, a cloud-seeding agent with a crystalline structure much like ice.

The chambers stand on steep mountain ridges facing the moist monsoon from south Asia. As wind hits the mountain, it produces an upward draft and sweeps the particles into the clouds to induce rain and snow.

“[So far,] more than 500 burners have been deployed on alpine slopes in Tibet, Xinjiang and other areas for experimental use. The data we have collected show very promising results,” a researcher working on the system told the South China Morning Post.

The system is being developed by the state-owned China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation – a major space and defence contractor that is also leading other ambitious national projects, including lunar exploration and the construction of China’s space station.

Space scientists designed and constructed the chambers using cutting-edge military rocket engine technology, enabling them to safely and efficiently burn the high-density solid fuel in the oxygen-scarce environment at an altitude of over 5,000 metres (16,400 feet), according to the researcher who declined to be named due to the project’s sensitivity.

While the idea is not new – other countries like the United States have conducted similar tests on small sites – China is the first to attempt such a large-scale application of the technology.

The chambers’ daily operation will be guided by highly precise real-time data collected from a network of 30 small weather satellites monitoring monsoon activities over the Indian Ocean.

The ground-based network will also employ other cloud-seeding methods using planes, drones and artillery to maximise the effect of the weather modification system.

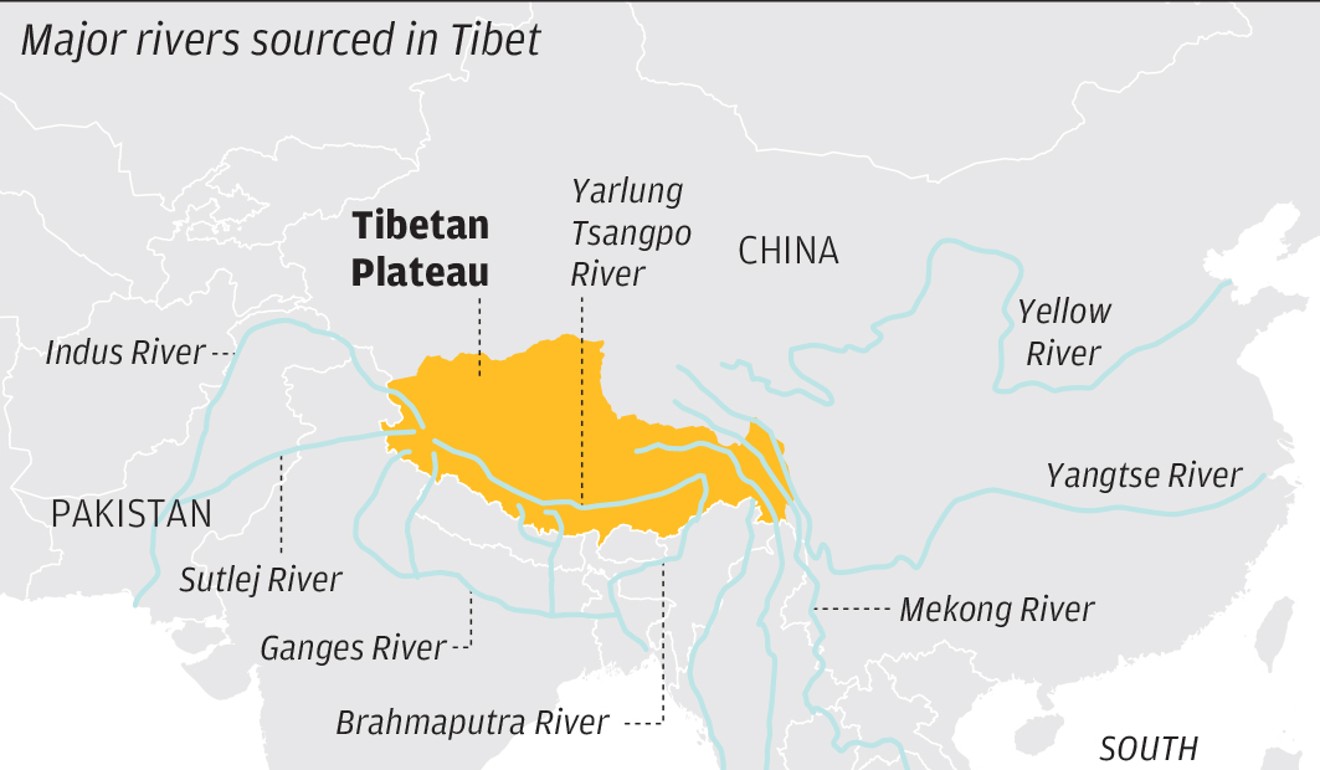

The gigantic glaciers and enormous underground reservoirs found on the Tibetan plateau, which is often referred to as Asia’s water tower, render it the source of most of the continent’s biggest rivers – including the Yellow, Yangtze, Mekong, Salween and Brahmaputra.

The rivers, which flow through China, India, Nepal, Laos, Myanmar and several other countries, are a lifeline to almost half of the world’s population.

But because of shortages across the continent, the Tibetan plateau is also seen as a potential flashpoint as Asian nations struggle to secure control over freshwater resources.

Despite the large volume of water-rich air currents that pass over the plateau each day, the plateau is one of the driest places on Earth. Most areas receive less than 10cm of rain a year. An area that sees less than 25cm of rain annually is defined as a desert by the US Geological Survey.

Rain is formed when moist air cools and collides with particles floating in the atmosphere, creating heavy water droplets.

The silver iodide produced by the burning chambers will provide the particles required to form rain.

Radar data showed that a gentle breeze could carry the cloud-seeding particles more than 1,000 metres above the mountain peaks, according to the researcher.

A single chamber can form a strip of thick clouds stretching across more than 5km.

“Sometimes snow would start falling almost immediately after we ignited the chamber. It was like standing on the stage of a magic show,” he said.

The technology was initially developed as part of the Chinese military’s weather modification programme.

China and other countries, including Russia and the United States, have been researching ways to trigger natural disasters such as floods, droughts and tornadoes to weaken their enemies in the event of severe conflict.

Efforts to employ the defence technology for civilian use began over a decade ago, the researcher said.

One of the biggest challenges the rainmakers faced was finding a way to keep the chambers operating in one of the world’s most remote and hostile environments.

“In our early trials, the flame often extinguished midway [because of the lack of oxygen in the area],” the researcher said.

But now, after several improvements to the design, the chambers should be able to operate in a near-vacuum for months, or even years, without requiring maintenance.

They also burn fuel as cleanly and efficiently as rocket engines, releasing only vapours and carbon dioxide, which makes them suitable for use even in environmentally protected areas.

Communications and other electronic equipment is powered by solar energy and the chambers can be operated by a smart phone app thousands of kilometres away for through the satellite forecasting system.

The chambers have one clear advantage over other cloud-seeding methods such as using planes, cannons and drones to blast silver iodide into the atmosphere.

“Other methods requires the establishment of a no-fly zone. This can be time-consuming and troublesome in any country, especially China,” the researcher said.

The ground-based network also comes at a relatively low price – each burning unit costs about 50,000 yuan (US$8,000) to build and install. Costs are likely to drop further due to mass production.

In comparison, a cloud-seeding plane costs several million yuan and covers a smaller area.

One downside of the burning chambers, however, is that they will not work in the absence of wind or when the wind is blowing the wrong direction.

This month, the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation signed an agreement with Tsinghua University and Qinghai province to set up a large-scale weather modification system on the Tibetan plateau.

In 2016 researchers from Tsinghua, China’s leading research university, first proposed a project – named Tianhe or Sky River – to increase the water supply in China’s arid northern regions by manipulating the climate.

The project aims to intercept the water vapour carried by the Indian monsoon over the Tibetan plateau and redistribute it in the northern regions to increase the water supply there by five to 10 billion cubic metres a year.

The aerospace corporation’s president, Lei Fanpei, said in a speech that China’s space industry would integrate its weather modification programme with Tsinghua’s Sky River project.

“[Modifying the weather in Tibet] is a critical innovation to solve China’s water shortage problem,” Lei said. “It will make an important contribution not only to China’s development and world prosperity, but also the well being of the entire human race.”

Tsinghua president Qiu Yong said the agreement signalled the central government’s determination to apply cutting-edge military technology in civilian sectors. The technology will significantly spur development in China’s western regions, he added.

The contents of the agreement are being kept confidential as it contains sensitive information that the authorities have deemed unsuitable to be revealed at the moment, a Tsinghua professor with knowledge of the deal told the Post.

Climate simulations show that the Tibetan plateau is likely to experience a severe drought over the coming decades as natural rainfall fails to replenish the water lost as a result of rising temperatures.

“The satellite network and weather modification measures are to make preparations for the worst-case scenario,” the Tsinghua researcher said.

The exact scale and launch date for the programme has not been fixed as it is pending final approval from the central government, he said.

Debate is also ongoing within the project team over the best approach for the project, he added. While some favour the use of the chambers, others prefer cloud-seeding planes as they have a smaller environmental footprint.

Ma Weiqiang, a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, said a cloud-seeding experiment on such a scale was unprecedented and could help answer many intriguing scientific questions.

In theory, the chambers could affect the weather and even the climate in the region if they are built in large enough numbers. But they might not work as perfectly in real life, according to the researcher.

“I am sceptical about the amount of rainfall they can produce. A weather system can be huge. It can make all human efforts look vain,” Ma said.

Beijing might not give the green light for the project either, he added, as intercepting the moisture in the skies over Tibet could have a knock-on effect and reduce rainfall in other Chinese regions.

0 Response to "China needs more water. So it's building a rain-making network three times the size of Spain"

Post a Comment