The administration plans to push “enduring” costs from the Overseas Contingency Operations war fund back into the base budget in future years.

The administration plans to push “enduring” costs from the Overseas Contingency Operations war fund back into the base budget in future years.Born as a budget-process necessity, the Pentagon’s war fund — né 2001 as the “emergency supplemental,” rechristened Overseas Contingency Operations in 2010 — quickly came under fire by critics who said it was used to hide the cost of conflict, and in the recent decade, even of basic base-building and vehicle-buying. Now the Trump administration says it wants to change what OCO pays for, to “get back to an honest accounting” for USwars. But some outside observers say some of the changes may actually undermine transparency.

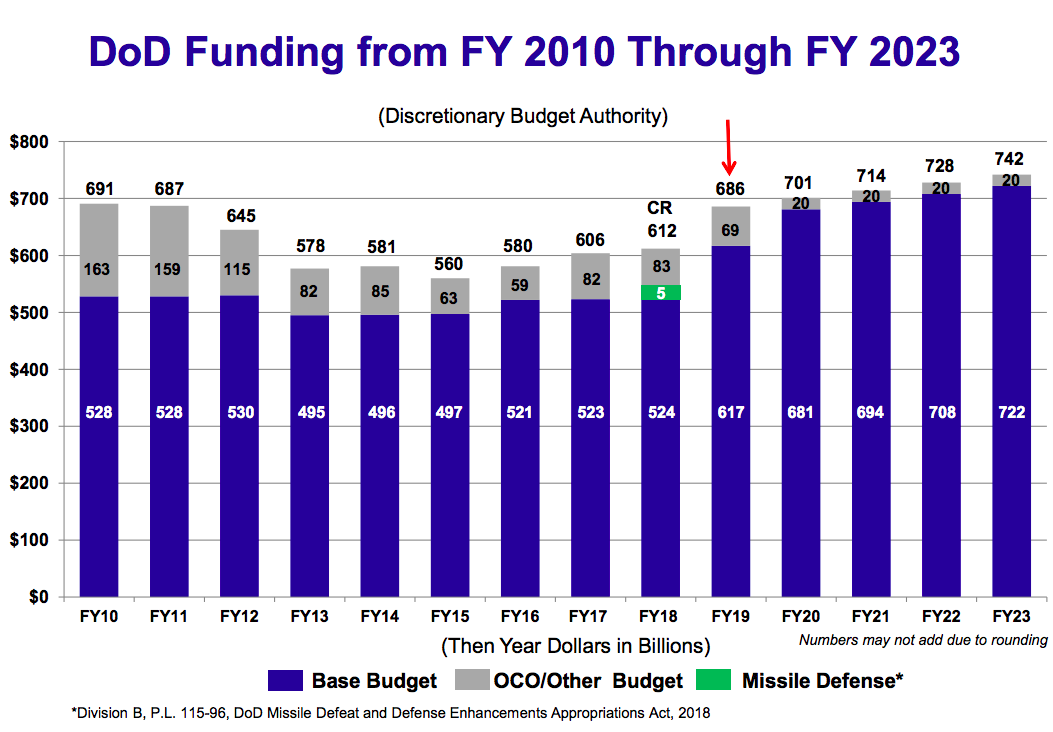

The first step to increasing transparency, officials within the government and outside analysts agreed, is to move the portion of OCO that the Pentagon explicitly acknowledged was funding base requirements — that is, costs unrelated to the wars — back where they belong. Two-year budget cap deal in hand, the Pentagon’s latest funding request started to do just that. Instead of asking for a planned OCO of $89 billion in 2019, the submission requests $69 billion, with the difference pushed back into the base budget.

But then starting in 2020, the administration wants to push annual OCO spending down to $20 billion or so. They’d do that by moving “enduring costs” of the conflicts into the base as well, and that’s where it could start to complicate efforts to track the costs of war.

The ‘enduring costs’ of war

It’s time to stop thinking of the bulk of the costs from America’s presence in the Middle East and Southwest Asia as contingencies, administration officials say, because a lot of those costs are here to stay. As such, they should be in the regular budget.

“What OMB has suggested going forward is once you get to ’20 and out, that we look at moving even more of OCO to base, that you look at some of those enduring costs that were created as part of OCO, but we’d keep, almost under any circumstance, going forward, and reduce the size of OCO to much more of the incremental costs.” the Pentagon’s CFO and comptroller David Norquist said Monday.

What would count as an enduring cost? The bases, the communications networks, and other infrastructure that underpin the regional campaigns against the Islamic State, al Qaeda, the Taliban and other extremist groups? Pentagon officials, OMB, and service budget leaders say they’re still figuring out what those buckets would be.

“There are regional costs that are going to be there whether or not” the U.S. is actively involved in a conflict, a senior OMB official said. “But I wouldn’t want to say that a base in Iraq or Afghanistan wouldn’t be considered contingency operations.”

Though the OMB official declined to be more specific as the conversation continues with the Pentagon, they said the types of costs would that belong in base budget are something of a “no-brainer list.”

The department’s own 2019 budget documents offer a clue: infrastructure is definitely up there. Though troop numbers are way down from the earlier years of the war in Iraq and the heights of the surge in Afghanistan, the budget overview book notes that OCO costs have not fallen at a commensurate pace, largely “due to the fixed, and often inelastic, costs of infrastructure, support requirements, and in-theater presence to support contingency operations.”

Exact figures aren’t available yet, as the department recalculates what’s OCOand base after the congressional budget deal, but the Pentagon had initially planned to ask for $20 billion in OCO for “in-theater support” alone.

Will this affect how much the Pentagon spends on wars?

At least initially, no. The plan is to move the expenses on “a one-for-one basis, reducing the size of OCO while staying within the same topline,” Norquist said.

That’s easier to say with the GOP holding both houses of Congress and the presidency. When the administration actually releases its 2020 budget proposal a year from now, they could be sending it down Pennsylvania Avenue to a Congress reshaped by the 2018 midterm elections.

If Democrats were to gain control of either house, there would be more pressure to match any increases in the defense base budget with increases on the domestic side. That was part of the pressure that encouraged the Pentagon to shunt expenses to OCO, which is not subject to procedural or statutory limits, in the first place.

That helped create the scenario the White House says it’s trying to rectify. The line between OCO and base is so “blurred” that it’s no longer a particularly useful distinction, said Todd Harrison, a defense budget expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Tracking those costs is a different matter

As fungible as the base/OCO distinction has become in recent years, OCO still remains the baseline for keeping track of what the U.S. has spent fighting in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria and elsewhere the last 16 and a half years. Any significant change to OCO would affect the government’s and independent analysts’ reporting.

The department’s own accounting of the wars closely tracks with OCO spending. The 2017 defense authorization bill ordered the Pentagon to sum up the total costs of the post-9/11 conflicts per taxpayer. In that report, the annual “’war‐related’ estimated costs” come in at several billion less than the enacted OCO fund for each country — likely a calculation reflecting the enacted OCO minus the varying level of base requirements that had been made their way into the war fund. (The Pentagon wasn’t able to to offer more details on how the report was calculated as of press time.)

For the years that didn’t yet have appropriations, the report used the requested OCO Afghanistan and Iraq funds without change.

OCO is also the starting point for outside analysts. The Brown Costs of War Project offers a more holistic tally of direct and indirect costs, including the State Department’s security operations, veterans’ health care, and interest on the debt incurred by war spending. But it, too, starts with OCO appropriations.

Cleaning up the distinction between OCO and base is, in some ways, helpful to tracking war spending. By moving the $17 billion the Pentagon had marked as OCO-for-base in early budget documents back into the base (and then a few billion more), you’re removing the “gimmicks,” and getting back to the “true costs of war,” the OMB official said.

But Neta Crawford, the co-director of the Brown Costs of War Project, said if those enduring expenses are moved into the base, it will make it significantly harder for the public and politicians alike to pull them out and understand what America’s overseas footprint costs.

“It’s been very difficult to track for years…and I think it’s going to get more difficult,” said Crawford, who last year published the study that found that paying off the debt on the wars could cost nearly $8 trillion by 2050, and that may be the basis of the president’s claims about spending in the Middle East.

The Pentagon will still incur the costs to maintain bases; operate command, control and communication networks; and sustain intelligence assets and other supporting capabilities in-theater, but they’ll be normalized. Normalization isn’t inherently negative, she said, but the worry is that they’ll disappear into the broader budget and will no longer be easily tied to the fights abroad. Lawmakers and independent auditors have criticized the Pentagon for not being transparent about everything from the administration’s strategies and readiness woes to the progress of the war in Afghanistan.

“Potentially this could be a benefit, but I doubt that will be the case,” Crawford said. “If you look at the trend, it’s toward diminishing the potential … to understand and report what we’re spending money on.”

0 Response to "It Could Get Harder to Track US War Spending"

Post a Comment