The National Defense Strategy does a service by getting the diagnosis right. But that is only the first step. To get the right prescription—the defense program—we will have to develop the operational concepts that link the ends sought with the means we can procure to achieve them.

The National Defense Strategy does a service by getting the diagnosis right. But that is only the first step. To get the right prescription—the defense program—we will have to develop the operational concepts that link the ends sought with the means we can procure to achieve them.A Marine HIMARS missile launcher fires from the deck of the USS Anchorage during the Dawn Blitz 2017 exercises.

Andrew Krepinevich, one of Washington’s leading strategists, was a career Army officer, a graduate of the legendary Andy Marshall’s Office of Net Assessment, and the longtime leader of the influential Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments. He has spent decades studying how to protect the United States and its allies. We asked him to analyze the Trump Administration’s new National Defense Strategy. He replied with this incisive analysis of what the NDS gets right and what needs to happen next. The strategy correctly diagnoses the strategic problem, Krepinevich writes, but what we need next is the prescription for how to solve it. Here’s his. Read on! The Editors

The National Defense Strategy rightly prioritizes great power competition as the biggest threat to U.S. security. This is perhaps its most significant contribution; waking us up from the collective security mindset that has captured the thinking of policy-makers following every major conflict going back to World War I.

Collective security assumes that all the great powers have bought in to the existing international system, that none seek to overturn it, and that all will defend against any challenge to it. Hence we witnessed the formation of the League of Nations after World War I and the signing of the Kellogg-Briand Pact to assure the eternal “renunciation of war”; the establishment of the United Nations after World War II along with the “Four Policemen” (an unlikely concert of the U.S., the U.S.S.R., what was still the British Empire, and not-yet-Communist China), and the protracted efforts after the Cold War to achieve some form of cooperative security.

In each case U.S. leaders misread the situation. Following World War I, Germany, Japan, and Italy rejected the international order and sought to impose a “New Order” of their liking. Following World War II the United States and the Free World were quickly confronted with the threat of Soviet and Communist expansionism. With the United States enjoying a dominant position following the Cold War, it was enticing to believe that the “end of history” was at hand and that the liberal democratic order had finally triumphed. But this only lasted until China amassed enough power and Russia recovered sufficient strength to challenge this order. Simply put, the United States has always been in an international system characterized by power politics, not collective security.

Between the two major revisionist powers, China is clearly the most formidable. China’s economy is roughly six times that of Russia’s, and is growing at a faster rate. Its military buildup dwarfs that of Russia. Relative to our own economy, China’s is far greater than the Soviet Union’s was at any point in the Cold War—and growing at a faster rate. Simply put, China’s potential power—hard and soft—is greater than that of Russia. Yes, Beijing has relatively few nuclear weapons compared to Moscow. That said, given time, there is nothing that prevents the Chinese from matching Russia’s arsenal.

Chinese weapons ranges (CSBA graphic)

From Strategy To Operations

So what do we do? Strategy is about setting priorities. What capabilities do we invest in, given our limited resources? Using a medical analogy, this means you must get the diagnosis right. Otherwise you risk investing increasingly scarce defense dollars in the wrong prescription—a suboptimal defense program—for dealing with the threat. Having come up with an accurate diagnosis, the National Defense Strategy must put the Pentagon on a path to make the appropriate adjustments to the defense program to employ our limited resources as efficiently and effectively as possible.

The link between the diagnosis and prescription is informed by operational concepts: how the military intends to deter and, if necessary, fight wars to defend our vital interests. During the Cold War, for example, our military developed detailed operational concepts to defend NATO’s European frontiers from a Soviet attack. The Army worked with the Air Force to develop its AirLand Battle concept to disrupt and defeat the successive echelons of a much larger Soviet force marching across Central Europe. The Navy pursued its Maritime Strategy and Outer Air Battle concepts to keep the Soviet fleet bottled up north of the Greenland-Iceland-UK gap and enable reinforcements to move by sea from America to Europe. The Marine Corps leveraged its maneuver warfare concepts with an eye toward rapidly reinforcing Norway to protect NATO’s northern flank. Informed by this detailed effort by our military services, senior civilian leaders in the Pentagon and in Congress were able to establish clear priorities for the defense program.

Today, unfortunately, these kinds of operational concepts for conflict with China and Russia simply do not exist. They are badly needed.

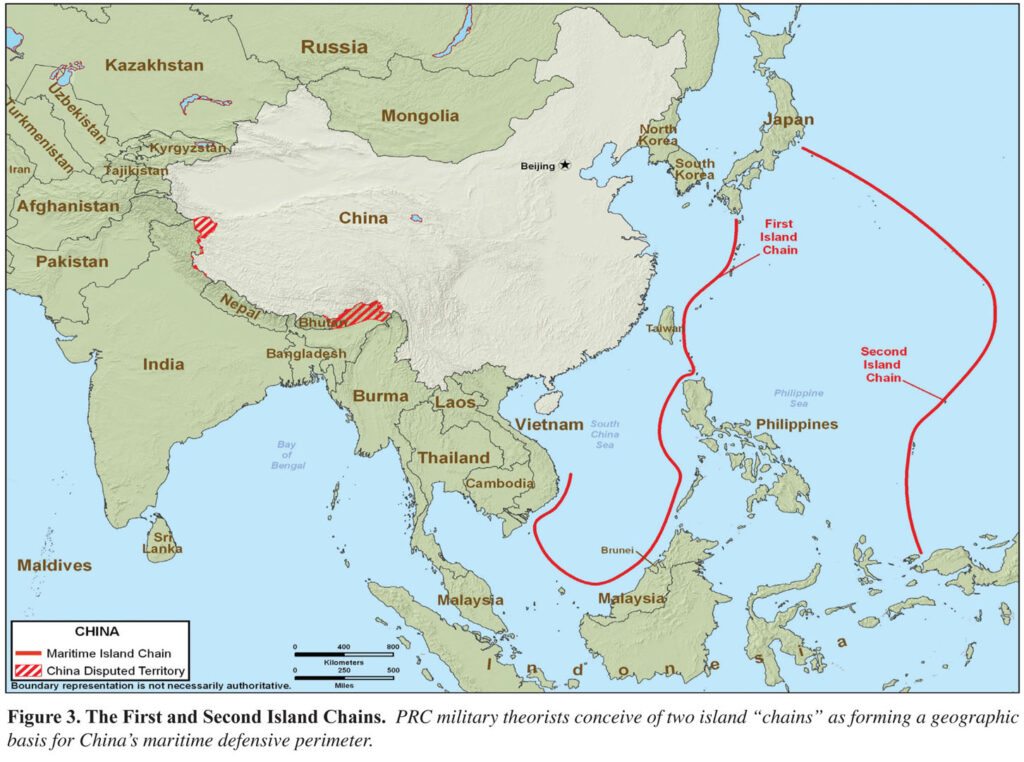

One proposed operational concept is Archipelagic Defense — which I have worked on with extensive input from colleagues and defense officials both here in the US and among our allies — for several years. Archipelagic Defense addresses the strategic question of how the United States, in concert with its allies and partners, can preserve a stable military balance in the Western Pacific. The objective is to help Japan, the Philippines, and Taiwan resist ongoing Chinese efforts to coerce and subvert them; to deter China from believing it can accomplish its aims through aggression; and, in the last resort, to defeat China should it choose the path of war.

Three countries—Japan, the Philippines, and Taiwan—comprise most of what China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) refers to as the First Island Chain. What should be the U.S. military’s operational concept for defending the chain?

Archipelagic Defense

The overall concept of Archipelagic Defense calls for a forward defense of the archipelago that comprises the Chain (hence the name). U.S. forces need to be deployed forward, on and around the islands before the conflict begins. It will likely be too difficult to bring reinforcements through airspace and waters which are within easy striking distance of PLA forces based in China and, increasingly, on South China Sea islands illegally seized by Beijing.

As the PLA believes it must seize control of the air and seas, as well as establish information dominance, in order to wage a major offensive campaign, deterring the Chinese requires U.S. and allied forces be clearly capable of preventing the PLA from creating these conditions.

To dominate the air and sea, the PLA will have to concentrate combat power at some point or points along the archipelago. American and allied forces must therefore also be capable of counter-concentrating sufficient forces to preclude this from occurring. To quote Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, we must “get there first with the most”— — troops, ships, planes and precision-guided weapons. This “concentration/counter-concentration” competition is a key feature of Archipelagic Defense, as it was of AirLand Battle during the Cold War and, indeed, Napoleon’s famous victories at places like Austerlitz.

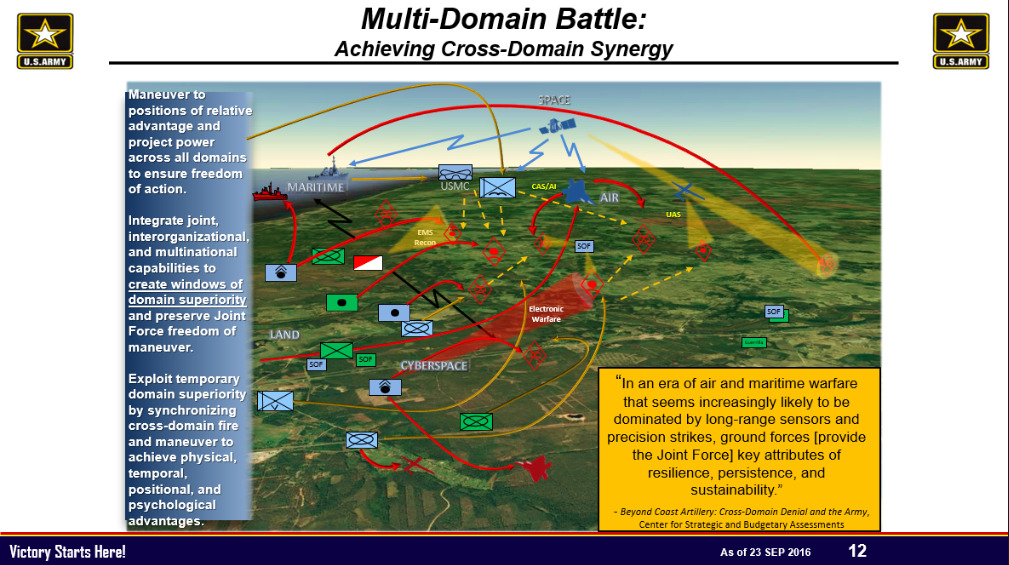

Winning this competition is essential. To do so, much like the concepts for defending Western Europe during the Cold War, Archipelagic Defense makes full use of each armed service in an important role. Ground forces, dug in and camouflaged on the islands, provide the backbone of the defense, enabling far more mobile air and maritime forces to serve as the principal operational reserve—the “counter-concentration” force. Finally, and crucially, U.S. long-range precision-strike forces, to include its bomber force, cruise-missile armed submarines, and Cyber Command function as a strategic reserve, able to concentrate capability over great distances with relative speed.

The most difficult adaptation Archipelagic Defense requires of the U.S. military is that ground forces positioned along the First Island Chain must emphasize cross-domain missions. Land-based air and missile defense forces — Patriot, THAAD, and future laser or railgun weapons – focus on preventing the PLA from establishing air superiority. Coastal defense — Army and Marine Corps shore-based anti-ship cruise missiles and anti-ship mine laying forces – work on denying the PLA Navy command of the seas, while electronic warfare systems emphasize hobbling Chinese efforts to achieve information dominance. U.S. Special Forces can also work with Philippine ground troops to create an irregular warfare force — a higher-tech and far more lethal version of the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance forces in Afghanistan after 9/11. Combined, these forces constitute a line of Anti-Access/Area Denial defenses, much like the A2/AD systems China is deploying against us.

An Army slide attempting to explain the service’s new Multi-Domain Battle concept

The Path Forward

All this is just the tip of the iceberg. A fully formed Archipelagic Defense concept would have to address other major planning issues, among them:

the dynamics of a mobilization race during a crisis;

how the concept would be adapted in the event of a war that becomes protracted;

and how the concept would be adjusted in response to shifts in the PLA’s posture and capabilities, as well as those of our allies and partners.

Make no mistake: Implementing Archipelagic Defense will require an increased investment by the U.S. and its allies and partners. There are encouraging signs from several allies, but they and other like-minded states are looking to Americans for leadership and for an understanding of what their role might be and how the U.S. armed forces can provide both the muscle and glue to enable their success. The recent budget agreement, with its significant increase in defense spending, is a good start.

While an effective Archipelagic Defense force cannot be done on the cheap, we can mitigate the cost. To start with, the new concept will take considerable time to put into effect. Just as NATO in 1962 was a far more capable alliance than it was when formed in 1949, Archipelagic Defense will not be realized overnight. This means the funding for it will necessarily be spread over time.

The Bottom Line: The National Defense Strategy does a service by getting the diagnosis right. But that is only the first step. To get the right prescription—the defense program—we will have to develop the operational concepts that link the ends sought with the means we can procure to achieve them.

0 Response to "How To Implement The National Defense Strategy In Pacific"

Post a Comment