THE arrival of T.N. Srinath into the middle class will take place in style, atop a new Honda Activa 4G scooter. Fed up with Mumbai’s crowded commuter trains, the 28-year-old insurance clerk will become the first person in his family to own a motor vehicle. Easy credit means the 64,000 rupees ($1,000) he is paying a dealership in central Mumbai will be spread over two years. But the cost will still gobble up over a tenth of his salary. It will be much dearer than a train pass, he says, with pride.

THE arrival of T.N. Srinath into the middle class will take place in style, atop a new Honda Activa 4G scooter. Fed up with Mumbai’s crowded commuter trains, the 28-year-old insurance clerk will become the first person in his family to own a motor vehicle. Easy credit means the 64,000 rupees ($1,000) he is paying a dealership in central Mumbai will be spread over two years. But the cost will still gobble up over a tenth of his salary. It will be much dearer than a train pass, he says, with pride.Choosing to afford such incremental comforts is the purview of the world’s middle class, from Mumbai to Minneapolis and Mexico City to Moscow. Rising incomes and the desire for status have, in recent decades, seen such choices become far more widespread in a host of emerging markets—most obviously and most spectacularly in China. The shopping list of the newly better off includes designer clothes, electronic devices, cars, foreign holidays and other attainable luxuries.

Many companies around the world are looking to India for a repeat performance of China’s middle-class expansion. India is, after all, another country with 1.3bn people, a fast-growing economy and favourable demography. And China’s growth is flagging, at least by the standards of the past two decades. Companies which made a packet there, both incomers such as Apple and locals like Alibaba, are seeking pastures new. Firms that missed the boat on China or, like Amazon and Facebook, were simply not allowed in, want to be sure that they do not miss out this time.

Enthusiasm about India is boundless. “I see a lot of similarities to where China was several years ago. And so I’m very, very bullish and very, very optimistic about India,” Tim Cook, Apple’s boss, recently told investors. A walk around the Ambience Mall in Delhi shows he is not the only multinational boss with big ambitions in the country. Indian brands like Fabindia, a purveyor of fancy clothes and crafts, are outnumbered by Western ones such as Levi’s, Starbucks, Zara and BMW. The slums that host a quarter of all India’s city dwellers feel a long way off.

Beyond the mall, Amazon has committed $5bn to establish a presence in the world’s biggest democracy. Alibaba has backed Paytm, a local e-commerce venture, to the tune of $500m. SoftBank, a Japanese investor, has funded a slew of start-ups premised on the potential buying power of India’s middle class. Uber, the world’s biggest ride-hailing firm, has hit the streets. Google, Facebook and Netflix are vying for online eyeballs. IKEA is putting the finishing touches to the first of 25 shops it plans to open over the next seven years. Paul Polman, boss of Unilever, has described India as potentially the consumer giant’s biggest market. Reports put out by management consultants routinely point to 300m-400m Indians in the ranks of the global middle class. HSBC, a bank, recently described nearly 300m Indians as “middle class”, a figure it thinks will rise to 550m by 2025.

But for some of the firms trying to tap this “bird of gold” opportunity, as McKinsey once called it, an awkward truth is making itself felt: a lot of this middle class has little money to spend. There are many rich people in India—but they number in the mere millions. There are a great many more who have risen above the poverty line—but not so far above it that they spend much on anything other than feeding their families. And there is less in between the two than meets the eye.

Missing the mark

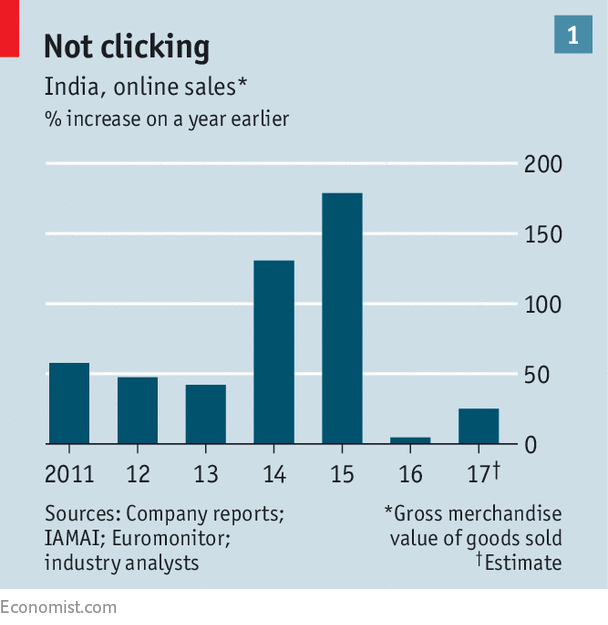

Companies that have tried to tap the Indian opportunity have found that returns fell short of the hype. Take e-commerce. The expectation that several hundred million Indians would shop online was what convinced Amazon and local rivals to invest heavily. Industry revenue-growth rates of well over 100% in 2014 and 2015 prompted analysts to forecast $100bn in sales by 2020, around five times today’s total.

That now looks implausible. In 2016, e-commerce sales hardly grew at all. At least 2017 looks a little better, with growth of 25-30%, according to analysts (see chart 1). But that barely exceeds the 20% the industry averages globally. Even after years of enticing customers with heavily discounted wares, perhaps 50m online shoppers are active in India—roughly, the richest 5-10% of the population, says Arya Sen of Jefferies, an investment bank. In dollar terms, growth in Indian e-commerce in 2017 was comparable to a week or so of today’s growth in China. Tellingly, few websites venture beyond English, a language in which perhaps only one in ten are conversant and which is preferred by the economic elite.

That now looks implausible. In 2016, e-commerce sales hardly grew at all. At least 2017 looks a little better, with growth of 25-30%, according to analysts (see chart 1). But that barely exceeds the 20% the industry averages globally. Even after years of enticing customers with heavily discounted wares, perhaps 50m online shoppers are active in India—roughly, the richest 5-10% of the population, says Arya Sen of Jefferies, an investment bank. In dollar terms, growth in Indian e-commerce in 2017 was comparable to a week or so of today’s growth in China. Tellingly, few websites venture beyond English, a language in which perhaps only one in ten are conversant and which is preferred by the economic elite.India has yet to move the needle for the world’s big tech groups. Apple made 0.7% of its global revenues there in the year to March 2017. Facebook, though it has 241m users in India, probably the most in the world in one country, registered revenues of just $51m in the same period. Google is growing more slowly in India than in the rest of the world. Mobile phones have become popular as their price has tumbled—but most handsets sold are basic devices rather than the smartphones that are ubiquitous elsewhere in the world.

Eating their words

Fast-food chains once spoke of a giant market. Their eyes were bigger than Indian stomachs. Despite two decades of investment McDonald’s has hardly any more joints in India than in Poland or Taiwan. The likes of Domino’s Pizza and KFC have struggled to come close to expectations that were once sky-high. Starbucks says it has big plans for India but has opened about one new coffee shop a month over the past two years, bringing its total to around 100—on a par with Utah or the United Arab Emirates. A new Starbucks opens in China every 15 hours, adding to 3,000 already operating.

Executives remain relentlessly upbeat in public—even if investments do not always follow. Anurag Mehrotra, boss of Ford India, told the Financial Times in May that car sales in India were set to double every three to five years. That would be an extraordinary change in fortunes: sales grew by less than 20% overall in the six years to 2016. There is one car or lorry for every 45 Indians, according to OICA, a trade group. The Chinese own five times as many. Motorbike sales have grown fast but only because their price has tumbled by 40% since 2000, points out Neelkanth Mishra of Credit Suisse, another bank.

India-boosters point to middle-class services that have taken off. With 20% annual growth in passengers, aviation is already booming at the rate Mr Mehrotra hopes to see in the car industry. But taken together, all India’s domestic airlines are no larger than Ryanair, the world’s fifth-biggest carrier, according to FlightGlobal, a consultancy. SpiceJet, an airline, says that 97% of Indians have never flown. A mere 20m Indians travelled abroad in 2015, about one in 40 adults.

Optimists also argue that the rapid growth of things like Chinese mobile-phone brands shows that the Indian middle class is out there and spending—just not on Western brands. Locally based fast-food chains that undercut McDonald’s or KFC have done much better than the new arrivals. But local consumer businesses face much the same problem as multinationals. Inditex, Zara’s parent firm, has 46 clothes shops in India, fewer than in Ireland, Lithuania or Kazakhstan. For the kind of goods the global middle class aspires to own at least, executives whether at global or local firms clock the number of potential customers at 50m and no more. Even selling basic consumer goods does not necessarily work. Hindustan Unilever, which purveys sachets of shampoo for just a few rupees, has seen virtually no sales growth in dollar terms since 2012.

“The question isn’t whether Zara or H&M can open 50 stores in India. Of course they can. The question is whether they can open 500,” says a banker who asks not be named, on the ground that it is best not to be seen questioning the Indian middle-class narrative. “You can try to push beyond the 50m people who have money, but how profitable would that be? Companies can expand for a time, but the limits to growth are getting obvious.”

The bullish argument that brought Western brands to India was basically this: although the country remains, for the most part, very poor, its population is so enormous that even a relatively small middle class is large in absolute terms, and fast overall growth will, as in China, quickly increase its size yet further. This assumes two things. One is that the middle class in India is the same relative size as in other developing countries where marketers have succeeded in the past. The other is that growth will benefit this middle class as much as other parts of the population. Neither is true in India, which as well as being poor is deeply unequal, and becoming more so.

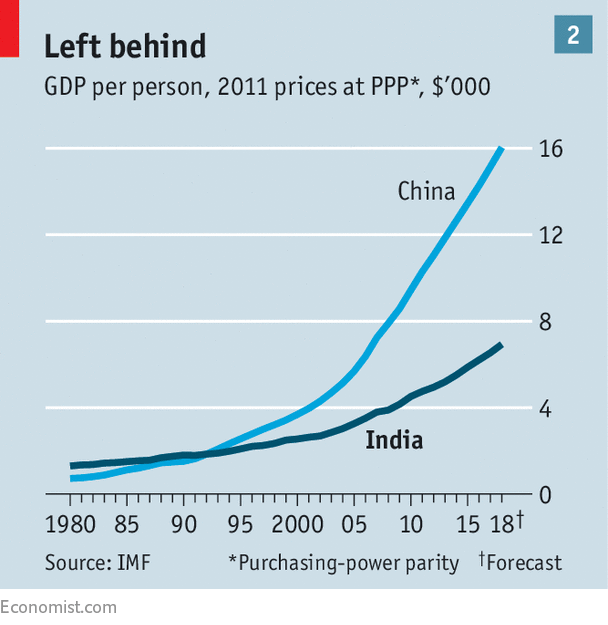

For all the talk of wanting to tap the middle class, no firm moving into India thinks it is targeting the middle of the income distribution. India’s mean GDP per head is just $1,700, and 80% of the population makes less than that. Adjust for purchasing-power parity by factoring in the cheaper cost of goods and services in India and you can bump the mean up to $6,600. But that is less than half the figure for China (see chart 2) and a quarter of that for Russia. What is more, foreign companies have to take their money out of India at market exchange rates, not adjusted ones.

For all the talk of wanting to tap the middle class, no firm moving into India thinks it is targeting the middle of the income distribution. India’s mean GDP per head is just $1,700, and 80% of the population makes less than that. Adjust for purchasing-power parity by factoring in the cheaper cost of goods and services in India and you can bump the mean up to $6,600. But that is less than half the figure for China (see chart 2) and a quarter of that for Russia. What is more, foreign companies have to take their money out of India at market exchange rates, not adjusted ones.Defining the middle class anywhere is tricky. India’s National Council of Applied Economic Research has used a cut-off of 250,000 rupees of annual income, or about $10 a day at market rates. Thomas Piketty and Lucas Chancel of the Paris School of Economics found in a recent study that one in ten Indian adults had an annual income of more than $3,150 in 2014. That leaves only 78m Indians making close to $10 a day.

Meagre market

Even adjusting for the lower cost of living, that is hardly a figure to set marketers’ heartbeats racing. The latest iPhone, which costs $1,400 in India, represents five month’s pay for an Indian who just makes it into the top 10% of earners. And such consumers are not making up through growing numbers what they lack in individual spending power. The proportion making around $10 a day hardly shifted between 2010 and 2016.

Another gauge is whether people can afford the more basic material goods they crave. For Indians, that typically means a car or scooter, a television, a computer, air conditioning and a fridge. A government survey in 2012 found that under 3% of all Indian households owned all five items. The median household had no more than one. How many of them will be anywhere near able to buy an iPhone or a pair of Levi’s if they cannot afford a TV set?

To get in the top 1% of earners, an Indian needs to make just over $20,000. Adjusted for purchasing-power parity, that is a comfortable income, equating to over $75,000 in America. But in terms of being able to afford goods sold at much the same price across the world, whether a Netflix subscription or Nike trainers, more than 99% of the Indian population are in the same league as Americans that count as below the poverty line (around $25,000 for a family of four), points out Rama Bijapurkar, a marketing consultant.

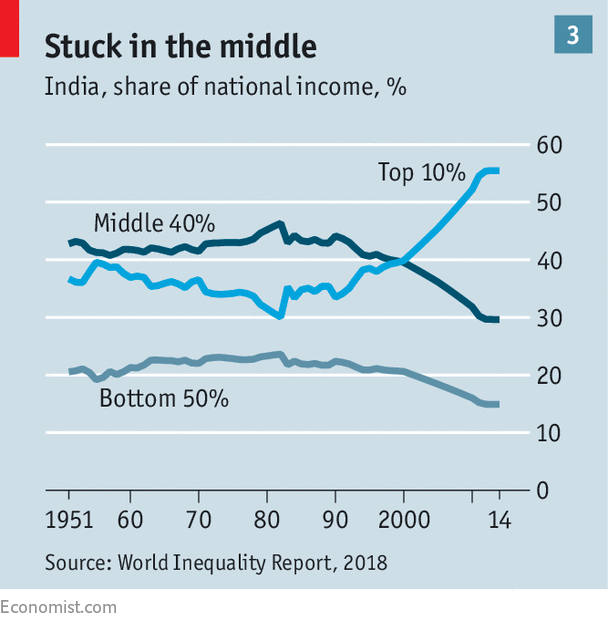

The top 1% of Indians, indeed, are squeezing out the rest. They earn 22% of the entire income pool, according to Mr Piketty, compared with 14% for China’s top 1%. That is largely because they have captured nearly a third of all national growth since 1980. In that period India is the country with the biggest gap between the growth of income for the top 1% and the growth of income for the population as a whole. At the turn of the century, the richest 10% of Indians made 40% of national income, about the same as the 40% below them. But far from becoming a middle class, the latter’s share of income then slumped to under 30%, while those at the top went on to control over half of all income (see chart 3).

The top 1% of Indians, indeed, are squeezing out the rest. They earn 22% of the entire income pool, according to Mr Piketty, compared with 14% for China’s top 1%. That is largely because they have captured nearly a third of all national growth since 1980. In that period India is the country with the biggest gap between the growth of income for the top 1% and the growth of income for the population as a whole. At the turn of the century, the richest 10% of Indians made 40% of national income, about the same as the 40% below them. But far from becoming a middle class, the latter’s share of income then slumped to under 30%, while those at the top went on to control over half of all income (see chart 3).Such economic success at the top leaves less for everyone else. Consider the 300m or so adults who earn more than the median but less than the top 10%. This group has fared remarkably badly in recent decades. Since 1980, it has captured just 23% of incremental GDP, roughly half what would be expected in more egalitarian societies—and less than that captured by the top 1%. China’s equivalent class nabbed 43% in the same period.

The rich get richer

Some have doubts about Mr Piketty’s methodology. But other surveys suggest pretty similar distribution patterns. Looking at wealth as opposed to income, Credit Suisse established in 2015 that only 25.5m Indians had a net worth over $13,700, equating roughly to $50,000 in America. And two-thirds of that cohort’s wealth was held by just 1.5m upper-class savers with at least $137,000 in net assets.

India’s middle class may be far from wealthy but the rich are truly rich. There are over 200,000 millionaires in India. Forbes counts 101 billionaires and adds one more to the list roughly every two months. It shows. The Hermès shop next door to the Honda dealership frequented by Mr Srinath sells scarves and handbags that cost far more than his scooter. Flats in posh developments start at $1m. In other emerging economies, there are fewer very rich and a wider base of potential spenders for marketers to tap.

In absolute terms, India has wealth roughly comparable to Switzerland (population 8m) or South Korea (51m). Although India’s population is almost the size of China’s, it is central Europe, with a population about the size of India’s top 10% and boasting roughly the same spending power, that is a better comparison. Global companies pay attention to markets the size of Switzerland or central Europe. But they do not look to them to redefine their fortunes.

Confronted by this analysis, India bulls concede the middle class is comparatively small, but insist that bumper growth is coming. The assumptions behind that, though, are not convincing. For a start, the growth of the overall economy is good—the annual rate is currently 6.3%—but not great. From 2002 China grew at above 8% for 27 quarters in a row. Only three of the past 26 quarters have seen India growing at that sort of pace.

Another assumption is that past patterns will no longer hold and that the spoils of growth will be distributed to a class earning decent wages and not to the very rich or the very poor. Yet the sorts of job that have conventionally provided middle-class incomes are drying up. Goldman Sachs, another bank, estimates that at most 27m households make over $11,000 a year—just 2% of the population. Of those, 10m are government employees and managers at state-owned firms, where jobs have been disappearing at the rate of about 100,000 a year since 2000, in part as those state-owned enterprises lose ground to private rivals.

Another assumption is that past patterns will no longer hold and that the spoils of growth will be distributed to a class earning decent wages and not to the very rich or the very poor. Yet the sorts of job that have conventionally provided middle-class incomes are drying up. Goldman Sachs, another bank, estimates that at most 27m households make over $11,000 a year—just 2% of the population. Of those, 10m are government employees and managers at state-owned firms, where jobs have been disappearing at the rate of about 100,000 a year since 2000, in part as those state-owned enterprises lose ground to private rivals.The remaining 17m are white-collar professionals, a lot of whom work in the information-technology sector, which is retrenching amid technological upheaval and threats of protectionism. In general, salaries at large companies have been stagnant for years and recruitment is dropping, according to CLSA, a brokerage.

Might those below the current white-collar professional layer graduate to membership of the middle class? This happened in China, where hordes migrated from the countryside to relatively high-paying jobs in factories in coastal areas. But such opportunities are thin on the ground in India. It has a lower urbanisation rate than its neighbours, and a bigger urban-rural wage gap, with little sign of change. It is not providing jobs to its young people: around a third of under-25s are not in employment, education or training.

There are other structural issues. Over 90% of workers are employed in the informal sector; most firms are not large or productive enough to pay anything approaching middle-class wages. “Most people in the middle class across the world have a payslip. They have a regular wage that comes with a job,” points out Nancy Birdsall of the Centre for Global Development, a think-tank. And women’s participation in the workforce is low, at 27%; worse, it has fallen by around ten percentage points since 2005, as households seem to have used increases in income to keep women at home. Households that might be able to afford luxuries if both partners worked cannot when only the man does.

Spent force

Across the income spectrum, households that do make more money tend to spend it not on consumer goods but on better education and health care, public provision of which is abysmal. The education system is possibly India’s most intractable problem, preventing it becoming a consumer powerhouse. Attaining middle-class spending power requires a middle-class income, which in turn requires productive ability. Yet most children get fewer than six years of schooling and one in nine is illiterate. Poor diets mean that 38% of children under the age of five are so underfed as to damage their physical and mental capacity irreversibly, according the Global Nutrition Report. “What hope is there for them to earn a decent income?” one senior business figure asks.

None of this leaves India as an irrelevancy for the world’s biggest companies. Whether India’s consumer class numbers 24m or 80m, that is more than enough to allow some businesses to thrive—plenty of fortunes have been made catering to far smaller places. But businesses assuming the consumer pivot in India is the next unstoppable force in global economics need to ask themselves why it already looks to have run out of puff—and whether it is likely to get a second wind any time soon.

This article appeared in the Briefing section of the print edition under the headline "The elephant in the room"

0 Response to "India’s missing middle class"

Post a Comment